Back Swart Dood Afrikaans Schwarzer Tod ALS Peste negra AN الموت الأسود Arabic الموت الاسود ARZ Peste negro AST Qara ölüm Azerbaijani قارا اؤلوم AZB Ҡара үлем Bashkir Чорная смерць Byelorussian

| Black Death | |

|---|---|

| |

| Disease | Bubonic plague |

| Location | Eurasia and North Africa[1] |

| Date | 1346–1353 |

Deaths | 25,000,000 – 50,000,000 (estimated) |

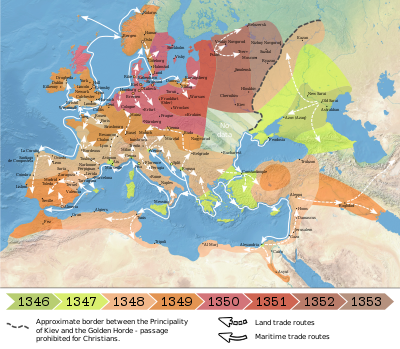

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Europe from 1346 to 1353. One of the most fatal pandemics in human history, as many as 50 million people[2] perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population.[3] Bubonic plague is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis and spread by fleas.[4][5] One of the most significant events in European history, the Black Death had far-reaching population, economic, and cultural impacts. It was the beginning of the second plague pandemic.[6] The plague created religious, social and economic upheavals, with profound effects on the course of European history.

The origin of the Black Death is disputed.[7] Genetic analysis points to the evolution of Yersinia pestis in the Tian Shan mountains on the border between Kyrgyzstan and China 2,600 years ago. The immediate territorial origins of the Black Death and its outbreak remain unclear, with some evidence pointing towards Central Asia, China, the Middle East, and Europe.[8][9] The pandemic was reportedly first introduced to Europe during the siege of the Genoese trading port of Kaffa in Crimea by the Golden Horde army of Jani Beg in 1347. From Crimea, it was most likely carried by fleas living on the black rats that travelled on Genoese ships, spreading through the Mediterranean Basin and reaching North Africa, Western Asia, and the rest of Europe via Constantinople, Sicily, and the Italian Peninsula.[10] There is evidence that once it came ashore, the Black Death mainly spread from person-to-person as pneumonic plague, thus explaining the quick inland spread of the epidemic, which was faster than would be expected if the primary vector was rat fleas causing bubonic plague.[11] In 2022, it was discovered that there was a sudden surge of deaths in what is today Kyrgyzstan from the Black Death in the late 1330s; when combined with genetic evidence, this implies that the initial spread may not have been due to Mongol conquests in the 14th century, as previously speculated.[12][13]

The Black Death was the second great natural disaster to strike Europe during the Late Middle Ages (the first one being the Great Famine of 1315–1317) and is estimated to have killed 30% to 60% of the European population, as well as approximately 33% of the population of the Middle East.[14][15][16] There were further outbreaks throughout the Late Middle Ages and, also due to other contributing factors (the Crisis of the Late Middle Ages), the European population did not regain its 14th century level until the 16th century.[a][17] Outbreaks of the plague recurred around the world until the early 19th century.

- ^ Lawton, Graham (25 May 2022). Wilson, Emily (ed.). "Plague: Black death bacteria persists and could cause a pandemic". New Scientist. London. ISSN 0262-4079. Archived from the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

lead numberswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Economic life after Covid-19: Lessons from the Black Death". The Economic Times. 29 March 2020. Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Haensch et al. 2010.

- ^ "Plague". World Health Organization. October 2017. Archived from the original on 24 April 2015. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- ^ Firth J (April 2012). "The History of Plague – Part 1. The Three Great Pandemics". jmvh.org. Archived from the original on 2 October 2019. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

lead originwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Wade, Nicholas (31 October 2010). "Europe's Plagues Came from China, Study Finds". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 November 2010. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ Sussman 2011, p. 354.

- ^ "Black Death | Causes, Facts, and Consequences". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 9 July 2019. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- ^ Snowden 2019, pp. 49–53.

- ^ "Mystery of Black Death's origins solved, say researchers". The Guardian. 15 June 2022. Archived from the original on 15 June 2022. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ Spyrou, Maria A.; Musralina, Lyazzat; Gnecchi Ruscone, Guido A.; Kocher, Arthur; Borbone, Pier-Giorgio; Khartanovich, Valeri I.; Buzhilova, Alexandra; Djansugurova, Leyla; Bos, Kirsten I.; Kühnert, Denise; Haak, Wolfgang (15 June 2022). "The source of the Black Death in fourteenth-century central Eurasia". Nature. 606 (7915): 718–724. Bibcode:2022Natur.606..718S. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04800-3. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 9217749. PMID 35705810. S2CID 249709693.

- ^ Aberth 2010, pp. 9–13.

- ^ Alchon 2003, p. 21.

- ^ Howard J (6 July 2020). "Plague was one of history's deadliest diseases – then we found a cure". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ Galens J, Knight J (2001). "The Late Middle Ages". Middle Ages Reference Library. 1. Gale. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search